Since my original post in 2015, I have dug deeper into the historical record and have come to understand that Truman’s decision, and the Japanese response, was more complicated. Useful for my rethinking was Marc Gallicchio’s book, Unconditional: The Japanese Surrender in World War II.

I now believe that while the atomic bombs were not the driving force in ending the war, they played a larger role than I originally acknowledged. It was both the Russian entry into the war and the atomic bombings, along with Japan’s deteriorating military and economic situation, that motivated the country to accept a slightly modified version of “unconditional surrender.” Evidence points to both the bomb and the Russian entry into the war as necessary conditions for Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. At the same time, my additional readings reinforced my belief that Truman was thinking beyond Japan, to the American-Soviet rivalry in the post-war world, when he decided to shun diplomacy and pursue a quick military ending of the war.

What follows is a complete revision of my original essays. I will post the revision, on the 76th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, in three parts. Part I covers Truman’s decision to use atomic bombs on Japan. Part II explores the Japanese Decision to surrender. In Part III, I speculate on the enduring legacy of the Hiroshima Myth. Part II will be posted tomorrow and Part III the next day.

SCRUTINIZING THE HIROSHIMA MYTH

Today marks the 76th anniversary of the dropping of the “Little Boy” atomic bomb on Hiroshima. As has been the case on every anniversary of the bombing, the use of the atomic bomb is being commemorated by politicians, media sorts, and most Americans as being responsible for ending the war, thus negating the need for an invasion of Japan’s home islands that would have resulted in as many as a million lost American and Japanese lives. This belief has achieved numinous status in the United States; most Americans accept it as an article of faith. It has become, as historian Christian Appy put it, the most successful legitimizing narrative in American history. There’s only one thing wrong with the Hiroshima narrative: it seriously exaggerates historical reality. There is perhaps no greater myth in U.S. history than the belief that the atomic bomb was the "winning weapon" that ended World War II. It’s what I call the Hiroshima Myth.

Despite doubts about the necessity to use the bomb expressed by a number of top military and political leaders at the time (and later in their personal reflections), challenges to the traditional Hiroshima narrative by several historians, and declining overall American attraction to nuclear weapons, the Hiroshima Myth remains deeply embedded in the consciousness of the overwhelming majority of Americans.

There’s much at stake in scrutinizing the Hiroshima Myth, for if the bomb didn’t end the war, then its use on Hiroshima, and especially Nagasaki, was wrong, militarily, politically and morally, profoundly so when one considers that these two cities were not vital military targets.

At the risk of being called unpatriotic, un-American, or worse, because the issue still touches raw emotions (Americans don't take kindly to questioning the morality of our country's purposes), I will attempt to refute the Hiroshima Myth about the winning weapon. In doing so, I can draw on a vast reservoir of historical writings on the subject. The record, some of it only recently discovered, includes a declassified paper written by a Joint Chiefs of Staff advisory group in June 1945, the personal accounts of top Japanese leaders, and various bits of documentary evidence uncovered by enterprising historians. These discoveries enable a more complete picture of bomb’s role in ending the war.

I preface this narrative by noting that historical accounts of Truman’s bomb decision, and Japan’s reasons for surrendering, are products of differing ideological interpretations, falling along conservative/liberal, Republican/Democrat, pro/anti-Roosevelt, anti-Communist, and inter-service rivalry fault lines, leading to differing conclusions suffused with heavy doses of supposition and speculation. While differing interpretations make it risky to draw definitive conclusions, I still stand on my claim that Truman’s reluctance to negotiate a diplomatic end to the war, and the timing of his decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, pointed more to his concerns about the Soviet Union than his hope of avoiding a costly invasion of the Japanese mainland. With regard to the timing of Japan’s decision to accept harsher terms of surrender than they desired, evidence points to it being the result of both the bomb and the Russian entry into the war, with the latter being what I argue was a more urgent concern.

This essay will be divided into three parts: Part I will examine Truman’s decision; Part II, Japan’s surrender decision; and, Part III my speculation on the impact of our enduring belief in the bomb as “the winning weapon” on American culture and how we approach national security.

PART I. WHY DID TRUMAN DECIDE TO DROP ATOMIC BOMBS ON JAPAN?

When Harry Truman became president on April 12, 1945, upon the death of President Roosevelt, he had little knowledge of international affairs and knew virtually nothing about the Manhattan Project that was developing an atomic bomb. On the first day of his presidency, Truman said in his memoirs, he was told by Roosevelt confidant James Byrnes that the U.S. was building an explosive “great enough to destroy the whole world.” He would be fully briefed on the bomb project on April 25 by Secretary of War Henry Stimson and General Leslie Groves, who had been put in charge of the Manhattan Project. Truman had only a rudimentary understanding of what an atomic bomb was, but what he did grasp was its potential for unlimited power. The idea of its omnipotence was ingrained into his consciousness early in his presidency.

As president, Truman, who had been selected by Roosevelt as his vice-president running mate after the nominating convention was deadlocked between Henry Wallace and Byrnes, inherited issues of momentous significance-- foremost of which were to lead the victory over Japan and decide what to do with the atomic bomb, which was nearing completion.

To bring victory in the Pacific, his advisers presented him three options. The first was diplomatic: negotiate an end to the war. Truman knew Japan was trying to get out of the war because we had broken its codes and were listening in on their communications. Tokyo had made overtures toward the Soviet Union, with whom it had signed a neutrality pact, in the hope that Moscow would help mediate a peaceful end to the war on terms favorable to Japan. Japanese leaders reasoned the Soviets offered the best hope for mediation since they might see this as an opportunity to limit U.S. influence in the region. The Japanese also tried to approach the Americans directly through Allen Dulles, who was Director of the OSS in Bern, Switzerland. Overtures were also made to neutral states Sweden, and Portugal.

Diplomacy was the least popular option among several of Truman's top advisers, particularly James Byrnes. They knew that Japan, whose air force and navy had been destroyed, and was short on food, supplies, munitions, and men to defend the home front (they were recruiting child soldiers and airmen), was close to defeat. Recognizing that the Japanese people were losing the will to fight, a U.S. military victory seemed imminent.

Other advisers, prominently Admiral Leahy, Joseph Grew, and Herbert Hoover urged diplomacy. Leahy disagreed with the advocates of an imminent military victory arguing that Japan was not as ready to capitulate as others assumed. It had some 800,000 soldiers on the homeland ready to fight to the death, still had millions of soldiers on the Asian mainland, and had thousands of suicide vehicles primed for use against the invaders.

Debate among advisers on Japan’s readiness to surrender centered on the terms to be offered, specifically, on the question of whether Japan would be allowed to keep its emperor and governing system or accept more restrictive terms dictated by the United States.

In striving to carry on with FDR's policies, Truman had adopted the former president's call for unconditional surrender, which Roosevelt had mentioned for the first time at the 1943 Casablanca Conference. Unconditional surrender was a popular war aim among war-weary, revenge-thirsty Americans, and it conformed to Truman’s view that Emperor Hirohito was a war criminal, but it complicated a negotiated end to the war because it was totally unacceptable to the Japanese, who were adamant about retaining their emperor, governing system and culture. Truman had little interest in revising a term so many Americans had rallied behind, especially when he believed Japan was playing such a weak hand.

|

| Sec. of Defense Henry Stimson |

Truman also understood that added pressure would be exerted on Japan and fewer American lives would be lost if the Russians joined the fight, which they had promised at the Yalta Conference to do three months after Germany's surrender. General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff, had told him at a June 18 meeting of the Joint Chiefs that Japan would likely capitulate after the Russian entry. With the atomic bomb project approaching a conclusion, however, Truman and Byrnes began to have second thoughts about Russia's entry into the war.

A test of the Plutonium bomb (“Fat Man”) was scheduled for the middle of July (scientists knew the Uranium bomb would work). Wanting the knowledge of a successful test before he met Stalin, Truman pushed the promised July 1 date for the Potsdam Conference back to July 15. It appeared he was coordinating the Potsdam meeting with the Alamogordo atomic test.

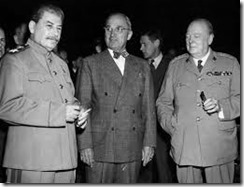

|

| Stalin, Truman and Churchill at Potsdam |

At Potsdam, Truman first saw Stalin on July 17 and quickly got his promise he would invade Japan as he had pledged at Yalta. In his Potsdam diary, Truman celebrated Stalin’s promise to “be in Jap war on August 15th” . . . “fini Japs when that comes about.” On July 18 he wrote to his wife: “I’ve gotten what I came for—Stalin goes to war on August 15 with no strings on it . . . I’ll say we’ll end the war sooner now and think of the kids that won’t be killed.”

These words suggest that Truman believed Russia's intervention might not only end the war, but obviate America's invasion plan. This may have been his thinking in the weeks leading up to Potsdam; it wasn't the case after Trinity. In truth, at Potsdam, with a strong prodding from Byrnes, the President was thinking about how best to keep the Russians out of the war. The challenge now was to end the war before, as Byrnes put it, the Russians could get "in on the kill?" Byrnes further believed that use of the atomic bomb would help persuade Russia to withdraw its troops from Eastern Europe after the war. Truman's reflections in his diary and to his wife appear to be playing more to posterity than truth.

Before Trinity another key figure in the bomb-use decision loop, in addition to Byrnes, appears to have been more focused on Russia than Japan. Polish physicist Joseph Rotblat reported that at a March 1944 dinner at physicist James Chadwick's house at Los Alamos, General Groves said in the course of casual banter around the dinner table: "You realize of course that the main purpose of this project is to subdue the Russians." Rotblat was shocked. He later wrote "until then I had thought that our work was to prevent a Nazi victory, and now I was told that the weapon we were preparing was intended for use against the people who were making extreme sacrifices for that very aim." (Quoted in Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin's American Prometheus, p. 284.)

|

| Truman and Byrnes Triumphal Return from Postsdam |

When Truman learned about the successful Trinity test on July 16, his demeanor at Potsdam changed. Fortified by the exciting news, his overriding focus at the conference shifted from the waning war with Japan to the looming Soviet threat. Russia's entry into the war was no longer believed to be needed to defeat Japan; it was now seen as a move that would further Stalin's grand design to extend communist control throughout the Northeast Asia. Truman’s focus abruptly shifted from military to political imagery: the bomb would give him, as he put it, “a hammer on those boys.”

Events at Potsdam pose a significant challenge to the Hiroshima Myth narrative for they make it clear Truman thought the end of the war was near, especially if the Russians joined in. The only real issue was how and on what terms. He apparently realized that if the bomb was not used before August 15, it might not be used at all. To ensure that the Japanese would not fall on their sword and surrender before the bomb could be used, Byrnes insisted that the final draft of the Potsdam Ultimatum retained the demand for unconditional surrender, which he knew was unacceptable to the Japanese, who had made it clear they were unwilling to accept a dramatic change in their political structure that would reduce the existence and authority of the emperor. | |

|

| General Leslie Groves |

Momentum for using the bomb had been building since General Groves was put in charge of the bomb project. Unsure of himself, Truman quickly fell under the spell of pro-bomb advocates Byrnes and Groves, who said in his memoir (Now It Can Be Told) that Truman always assumed the bomb would be used when ready. He characterized the president as being pulled along “like a little boy on a toboggan.” While conveying the technological and bureaucratic momentum of the of the bomb project, Groves’ characterization exaggerated Truman’s malleability, for the President was committed to the idea that Japan should surrender unconditionally and be subject to the authority of a supreme U.S. commander after the war, but it does capture Truman’s allure for The Gadget.

It also suggested Truman did not consider alternatives. This isn’t true. Six of the seven five-star generals and admirals at the time, including Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in Western Europe and General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Pacific, and Fleet Admiral William "Bull" Halsey believed use of the atomic bomb was “completely unnecessary:” Japan was already defeated, realized it, and was likely to surrender even before any American invasion could be launched.

General George C. Marshall also had serious reservations. If the bomb were to be used, he though it should be dropped on a purely military target; if this didn't induce surrender, then the Japanese should be warned before a second bombing. Believing Japan’s defeat was imminent Navy Chief of Staff Admiral Leahy insisted that even an invasion of Japan was not necessary to end the war.**

There is no evidence Truman gave serious consideration to any of these alternative views. The power surge he got from Trinity led him to shift priorities. Already inclined to heed the advice of Byrnes, whom he had named Secretary of State, he now listened more intently to the Secretary's urging that we should think beyond the war—to the rivalry that was sure to develop with the Soviet Union. If the Russians invaded Japan and were instrumental in forcing Tokyo’s surrender, then they would be in a position after the war to not only extend communist control in the Far East, including in China and Manchuria, but also in Eastern Europe where Red Army troops were still stationed. General Groves echoed Byrnes' concerns about Soviet expansionism, which to him was always the main reason why the bomb's creation was necessary,*** as did Secretary of Navy James Forrestal, who warned of the menace of Russian Communism and its attraction for decimated, destabilized societies in Europe and Asia.

Byrnes believed the display of awesome American power would make the Russians more "manageable" on critical issues involving the independence of Poland and other East European states. Enamored with the bomb’s omnipotence, he thought it would enable the U.S. to pretty much dictate terms after the war, as he put it, enable us to control events both large and small. The desire to showcase the bomb’s destructiveness lay behind the decision to spare a few Japanese cities from the fire bombings to provide “virgin targets” where the effects of the bomb could be clearly seen (and studied). It also led the Interim Committee to reject recommendations to demonstrate the bomb, drop it on a sparsely populated area, or warn the Japanese in advance. The goal was to maximize its shock value. (The Interim Committee didn’t appear to have discussed the number of Japanese civilians who might be killed by atomic bombs.)

So, once he has his "master card" in his hands, Russian entry no longer looked so good to the President. Neither did recommendations he was getting from Stimson and others to share bomb knowledge with Stalin in order to make international control of the weapon after the war more feasible. Truman wasn't interested in such a sharing. At Potsdam, he only casually mentioned to Stalin that the U.S. had a "new weapon of unusual destructive force." Stalin responded that he was glad and hoped the U.S. would make "good use of it against the Japanese." (Stalin, of course, already knew about the bomb from German emigre Klaus Fuchs at Los Alamos and at least two other spies at other Manhattan Project facilities who provided documents to Soviet agents.)

|

| Telling Sailors About "The Greatest Thing in History" |

The availability of the bomb and concern about Soviet expansionism played heavily on Truman's mind as he instructed the Target Committee to use it as soon as it could be made ready. General Groves, the head of the Committee, was determined to use it before the Russians entered the war. Truman said he ordered its use on July 25 while still in Potsdam, though he has also claimed he gave the final order while at sea returning from Europe, which would have made it on or after August 2. Historian Barton Bernstein, a foremost expert on the bomb decision, concludes that Truman decided the July 25 order would stand unless Japan made a satisfactory response to the Potsdam Ultimatum. This was probably "an informal but clearly understood arrangement" that was later transformed by Truman and his ghost writers into a "firm order." The evidence suggests that Truman had no hand in the written directive to use the bomb nor did he issue an official instruction to drop it. (The only written directive to use the bomb came in August 1945 from General Thomas Handy who was acting Chief-of-Staff while General Marshall was away at Potsdam.)

The Target Committee selected four cities: Hiroshima, Kokura, Nagasaki, and Niigata. None of these were of much military significance. Operational control was given to Groves who made the actual decision to drop the "Little Boy" on Hiroshima on August 6. In a rush to drop the second bomb, Groves pushed up the date to August 9. Despite a fuel pump problem that should have delayed the mission, Bock's Car took off in the morning of the 9th. The "Fat Man" bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, instead of the intended target, Kokura, which was heavily clouded over. This was just one day after the Russians had entered the war.

After Nagasaki, to give Japan a reasonable amount of time to surrender, and restore his control over the bombing process, Truman ordered that no additional bombs would be dropped without his expressed permission. He was reportedly deeply troubled by visuals of the two devastated cities and had little stomach for another bomb. Henry Wallace, Truman’s Secretary of Commerce wrote in his diary that the President had said he didn’t like the idea of wiping out another 100,000 people, including “all those kids.”****

This may be the great irony of the Hiroshima narrative. The atomic bomb may in fact have been instrumental in ending the war, not so much by shocking the Japanese into surrendering, but by shocking Truman into slightly modifying the surrender terms to allow Japan to keep its emperor, though subject to the Supreme U.S. Commander authority.

Historical evidence suggests that the Japanese War Council ultimately decided to accept revised surrender terms on August 14 for two reasons: first, they had born witness to two horrific atomic bombs (more on this in Part II); and, second, they were not fully aware of what the emperor and the entire government being subordinate to the Supreme Commander would ultimately mean: a condition that would reduce the emperor to a symbol without authority and power.

Truman thus got what he wanted: he showcased the bomb and by refusing to make substantive concessions about the emperor’s role after the war, he stayed true to the original purpose of unconditional surrender and to American war objectives.

The evidence thus points to the main motive in Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb against Japan as not primarily to end the war and avoid a bloody land invasion, but to contain and intimidate the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, as I will argue in Part II, the bomb did influence Japan’s War Council, after intervention by Emperor Hirohito, to accept surrender terms less favorable than it was holding out for. As such, it's correct to think of its use not so much as the last act of World War II, but the first act of the Cold War.*****

There has been much speculation as to why President Truman fell in line so easily with the pro-bomb advocates. Some, like General Groves, point to bomb-use momentum he inherited. Others believe he misunderstood the nature of the bombing, believing, based on comments he made, that Japan would be given advanced warning and the bomb would be dropped only on a military target, hence minimizing the loss of civilian lives. Some histories emphasize that with so much money invested in producing the bomb, and all the use machinery in place, the American people would fully expect that the bomb would be used, if for no other reason than to justify the expenditure.

Some historians have focused on Truman’s alleged racist views toward the Japanese. The president seemed to have been swept into the anti-Japanese maelstrom of race hate and revenge. To most Americans, the Japanese were “subhuman,” or as Truman put it in his diary, “savages--ruthless, merciless, and fanatic.” (Magazines and newspapers routinely depicted Japanese as apes, insects and vermin. “The only good Jap is a dead Jap,” was a common refrain.) They were a people so loyal to the emperor that they would fight to the bitter end. Besides, this was “total war.” The line between combatants and civilians had long been broached. Given the prevailing image of the Japanese, it was easy for Americans to believe that nothing short of near extermination could force their surrender. These sub-humans deserved the worst.

In their book Hiroshima in America, Robert Jay Lifton, a psychiatrist, and Greg Mitchell illuminate elements of Truman’s personality they believe made him willing to go in the atomic direction Byrnes was taking him. The insecure Truman had long tried to counter perceptions of him as weak-- a "sissy" he was often called in school-- with displays of toughness. They argue that Truman’s insecure psychological style lent itself to a considerable capacity for numbing and denial of death. They say he tended toward premature decisiveness when under stress, which would block our remorseful reflections of any kind. So constituted, he was disinclined to probe his advisers for latent disagreement. He lacked the self-confidence needed to resist the pressures of assertive men like Byrnes and Groves.

Whatever his motivation, given all the momentum built up to use the bomb, Truman would have to have been a man of iron will to say no. He responded to pressure from advisers who out of concern for the consequences of Soviet entry into the war urged a quick Japanese surrender. Since prospects for a negotiated end to the war under the conditions specified in the Potsdam Declaration seemed slim, the bomb appeared the best option. Truman went to his grave insisting he never had a single regret or a moment’s doubt about his decision.

The decision to use the atomic bomb against Japan thus played more to Moscow than to the widely-held belief in the U.S. that it was used to end the war before a bloody land invasion that would have resulted in a heavy loss of lives on both sides, a mercy killing that prevented even greater suffering (i.e., The Hiroshima Myth). This, of course, does not mean Truman was not concerned about the loss of American lives. In his view, the bomb decision served both purposes. In the end, like so many others, Harry Truman was drawn to the bomb’s ultimate power and feared the consequences of not using it.

_______________________

*It is important to note that the expected loss of American lives was far less than the inflated numbers tossed around after the war. In a widely read intimate history of the bomb decision, published by Secretary of War Stimson in the February 1947 issue of Harper's Magazine, the War Secretary wrote he was informed the invasion would cost "over a million American casualties." The New York Times bought into Stimson's projection and atomic bombing justification, observing that "by sacrificing thousands of lives" the atomic bomb "saved millions." In his 1955 memoir, Truman put the number of American lives that would have been lost at “half a million.” Most Americans believe the highly inflated numbers brandished around after the war. Clearly the lives-saved numerology game plays well to the claim that the bomb’s use was necessary and morally justified. The "million lives saved" myth is a key component of the official Hiroshima narrative.

** This view has been voiced by a number of historians who cite the 1947 Strategic Bombing Survey, which concluded that the Japanese would have surrendered “certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to November 1 1945—even if the atomic bomb had not been dropped, the Russians had not entered the war, and no invasion had been planned or contemplated.” Other historians countered that the USSBS report was marred by serious errors because its main objective was to make a case for an independent air force and was written hastily with little regard for contradictory evidence.

*** As early as 1944, Groves had admitted to a Manhattan Project scientist that the development of atomic bombs was really meant to subdue the Soviet Union, because the U.S. would have exclusive possession of nuclear weapons after the war.

**** Perhaps in an effort to provide moral cover for his decision, Truman wrote in his memoirs that he had "told Stimson that the bomb should be dropped nearly as possible upon a war production center of prime military importance." He also described Hiroshima as "a military base," chosen to avoid civilian casualties "insofar as possible."

*****This view is consistent with the new left, revisionist history of the bomb decision advanced by Gar Alperowitz in his 1965 book, Atomic Diplomacy, in which he argued that the bomb was used to intimidate the Russians. Alperowitz contends Truman knew Japan was trying to surrender but was reluctant to let them do so until he dropped the bomb. Critics accuse Alperowitz of underestimated Japanese determination to preserve the emperor’s position and with it their political structure in the summer of 1945.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting!